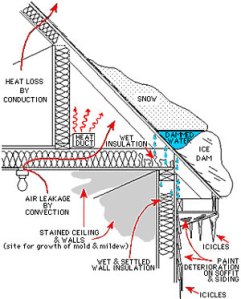

The Umpteenth Law of Thermodynamics says every speck of matter in the universe is trying to arrive at the same uniform temperature. Hot things are forever shedding heat, and cold things are forever absorbing it. We try to arrange our homes in a way that prevents heat from radiating out into the cold air, snow, trees, cars, and the black universe. But heat escapes nonetheless.

And the warmer your house is, the faster heat will pulse outside to achieve harmony with coldness. That’s why it saves energy to turn the thermostat down when you’re sleeping or working: The closer the inside temperature is to the outside temperature, the less ambitious the heat is about cooling off.

The big, fat caveat, especially here in Maine where many old houses still hiss and thump along with steam heat, is that mass messes up the thermodynamics (which weren’t particularly tidy to begin with). Steam has to heat up hundreds of pounds of cold, iron radiator before much heat can pass into the air and the walls and the toilet seat. Same goes for radiant heat in concrete floors: The heating mass takes a long time to cool off; then a long time to heat up.

Even so, turning the thermostat up and down for an old steam system doesn’t make the furnace work any “harder,” or burn more fuel in the long haul. It truly does save energy (money), says the Department of Energy–about 1% savings per degree if you turn down for eight hours a day.

The problem is that you may not love the sluggish changes in temperature that result from a massive heating system: By the time the bathroom gets warm in the morning, it’s time to go to work.

The cool news is that new thermostats are much better at physics than I am. Brainy new appliances can continuously calculate the ideal timing of your furnace’s bursts of effort.

![Heat being heat. [PD] Wikimedia](https://geekrealtyblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/800px-american_school_-_the_burning_of_the_harbor_masters_house_honolulu_oil_on_panel_1852_honolulu_academy_of_arts.jpg?w=300&h=171)

![[PD] wikimedia](https://geekrealtyblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/psm_v24_d637_indian_hut_in_the_tiera_caliente.jpg?w=300&h=226)

![Glickman%20Library[1]](https://geekrealtyblog.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/glickman20library1.jpg?w=300&h=133)