My husband didn’t hear me the first 200 times I said, “Add water to the steam boiler reallllly slowly.” He’s from a part of the country where the populace prefers less catastrophic methods of home heating. So when the boiler quit due to low water, he descended to the basement, located the cold water valve, and let ‘er rip.

My husband didn’t hear me the first 200 times I said, “Add water to the steam boiler reallllly slowly.” He’s from a part of the country where the populace prefers less catastrophic methods of home heating. So when the boiler quit due to low water, he descended to the basement, located the cold water valve, and let ‘er rip.

Steam heat is one of those Northeastern traditions, born of cheap coal and hard winters. You shoveled coal into a boiler, and the resulting steam swarmed up through cast iron pipes to heat colossal, iron radiators. Sure, the radiator valves leaked a little, and the pipes hammered, and every week or so you had to add water to the boiler reallllly slowly, but… inertia. And in the 1970s when people began to give one tiny darn about fuel efficiency, it became apparent that steam boilers would never measure up… well… The heat was so nice, pulsing so steadily from those masses of iron.

Adding to the comfy inefficiency of steam, the radiators tend to be too big. They were installed in the early part of the 20th century, when houses had single-pane windows and no insulation. During the decade after the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918-1919, radiators got even huger: They were sized for houses in which the windows were left open at night, all winter, to blow away the germs.

As homeowners insulated and weatherized over the years, the mismatch chafed. Most steam radiators retain at least some flaking paint not because it’s pretty, but because slapping on metallic paint reduces a radiator’s effectiveness–intentionally. Ditto for those boxy radiator covers. In apartment buildings of a certain age, there’s an entire cottage industry bent on out-witting the infernal steam radiators.

Well, my husband has beaten ours decisively. Cold water struck the red-hot intestines of the iron boiler, which shattered just the way the manual said they would. A pool of rusty water spread like furnace-blood across the floor.

I made a quick survey of the inefficiencies in this system:

Inefficiency of the boiler itself: Steam boilers always waste at least 15% of their fuel. Because my house is well insulated, my boiler was actually too big, further eroding its efficiency.

Heat loss to basement from mammoth, cast iron pipes: A lot, even though I wrapped them in insulation.

Radiator inefficiency: Between the dust, the paint, and boxy covers, a ton. Maybe 30-40%.

These various losses are apples and oranges, but they add up to a rotten fruit salad.

This house turns 100 this year. I think a century is long enough for the original technology to prove itself. We’re giving it a 21st Century Viessmann 222F direct-vent gas boiler with 98% fuel efficiency, three pump speeds, outdoor temperature sensor, and built-in domestic hot water tank–along with some flat-panel radiators, each one a zone unto itself.

We’re leaping a hundred years in a week.

What could go wrong?

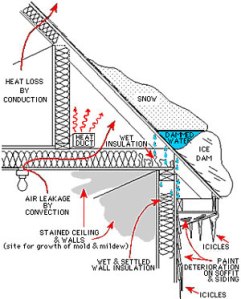

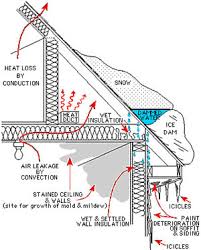

This picture is worth a thousand words. Just do this, and you won’t have to read the rest of the post. But by all means if you prefer reading about stuff you should do, rather than actually doing it, read on. We’ve all been there.

This picture is worth a thousand words. Just do this, and you won’t have to read the rest of the post. But by all means if you prefer reading about stuff you should do, rather than actually doing it, read on. We’ve all been there.

That facebook post about opossums eating 1 billion ticks an hour: Is it true?

That facebook post about opossums eating 1 billion ticks an hour: Is it true?